The ‘art’ of keeping sane: a PhD caught in a pandemic

To think that a month ago, I lived happily amidst a few people, starting my days early in the sticky warmth of tropical sunshine, enjoying cups of chai, watching for birds, picking up and playing with wind-dispersed seeds. All of this in a small village in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands on the far east of mainland India.

A complex ecological diversity and social history weave the fabric of these islands. From rainforest to sea, you tread through mangroves and dive between corals. On land, you are warmly invited into different cultures, languages, religions, foods and livelihoods.

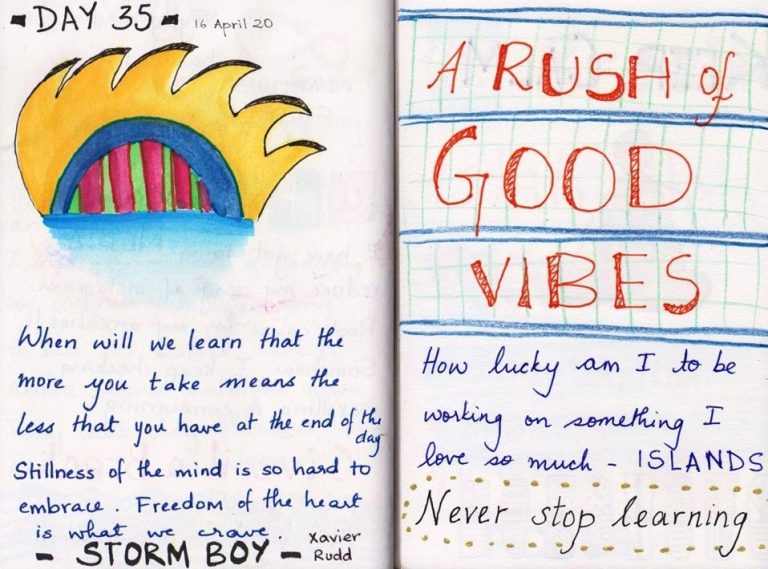

Unsurprisingly, the islands are changing rapidly, with growing pressures for infrastructure development. Tourism is a major employment sector in the islands, a livelihood for thousands. While tourism is economically critical to the islands, the pressures from its unplanned development come at a serious environmental cost. A holistic balance between the two dimensions is required. I am a social-ecologist investigating the conflicts between conservation and development in rapidly developing islands in the Indian Ocean. The Andamans are the focus of my PhD.

I spent two months in the Andamans this year, familiarising myself with the local context, systematically making new contacts for my research interviews, adapting in this concoction of mixed cultures and discovering that everything takes longer than I thought.

The Andamans gave me a sense of calm. Running down the street to catch the 19:05 full moonrise and hoping for bioluminescence on moonless nights. As if leafing through a children’s book, I lived a new adventure every day.

Breathing. Exploring. Simply Living.

I transport myself to the islands mentally, now that I sit miles away in the landlocked-locked-down Bangalore, my home city. I returned home unexpectedly in early March to renew my passport, thinking that I would be in the city for 3 days, and then quickly escape back to the islands.

My flight got cancelled, fieldwork cancelled, PhD left uncertain.

Having no research data from the islands meant that I needed to redirect my thinking. One of my supervisors told me that I might have to mentally prepare for a lockdown for what could be an entire year! The only temporary feasible solution would be to work on a review paper related to my research.

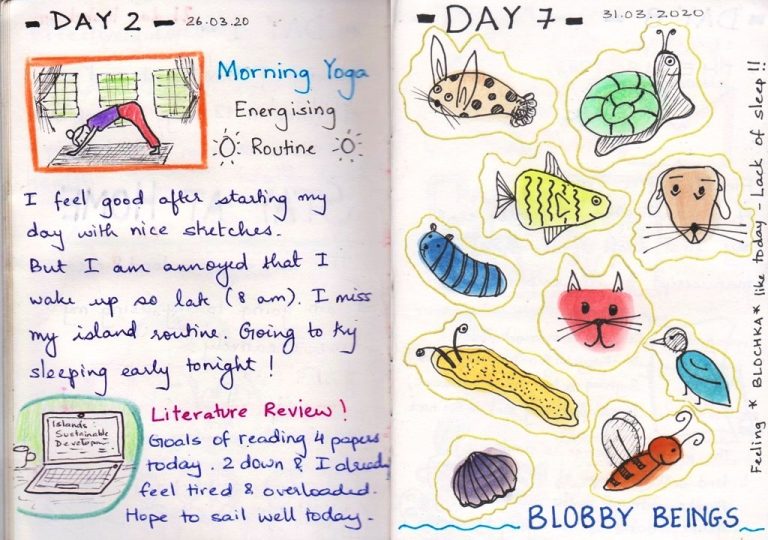

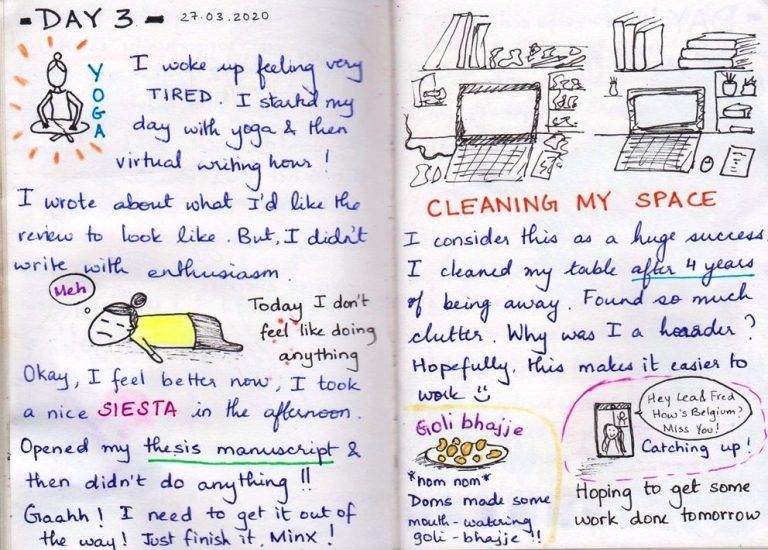

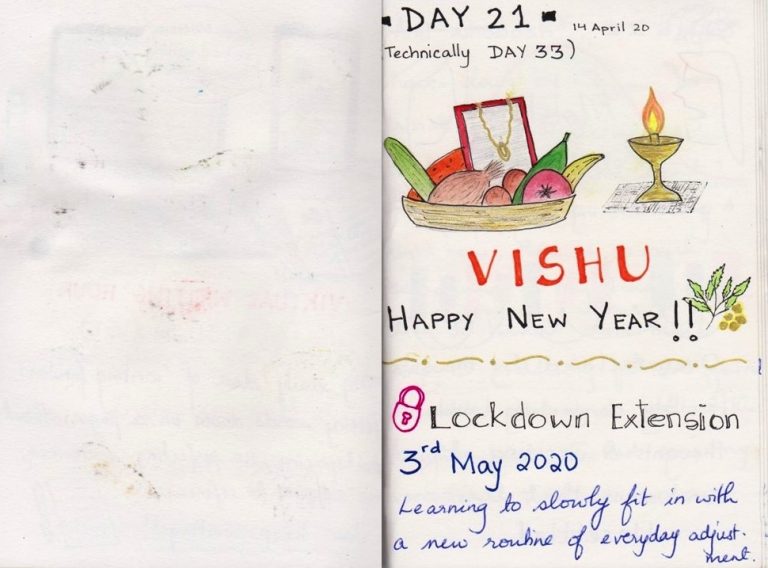

Then, the Government of India announced a 21-day lockdown, which has now been extended (indefinitely?). Day 1: ‘I will make the most of this situation’, I wrote. Two tasks – the review and a manuscript from a previous project. The list quickly proliferated to five different projects that require much time and incredible amounts of energy.

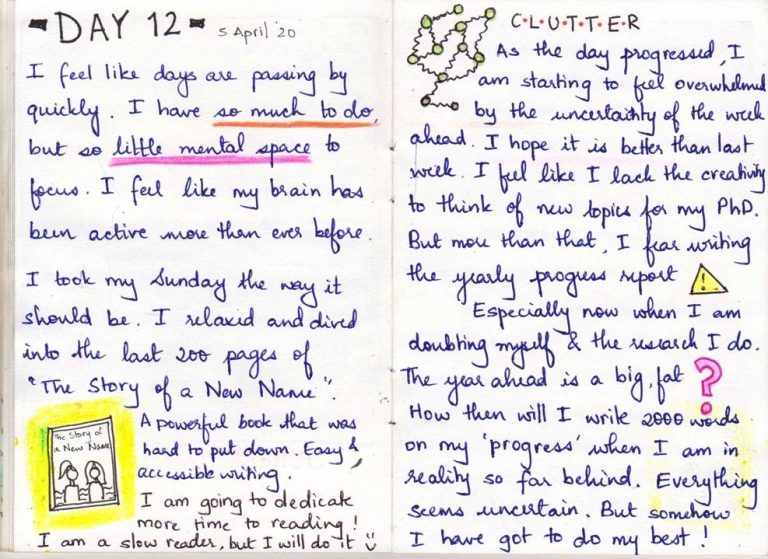

For PhD students like me, time can be easily stretched because of blurry deadlines and the pressure of being the key decision-making player. You don’t have anyone but yourself to report to everyday. While I am thankful for caring supervisors, and sometimes for the flexibility in time and personal space, the PhD is full of uncertainty, especially now. We often wait for motivation to arrive at our front door, hoping that this will make us feel productive. Sadly, motivation doesn’t work like that. You’ve got to start before you feel ready.

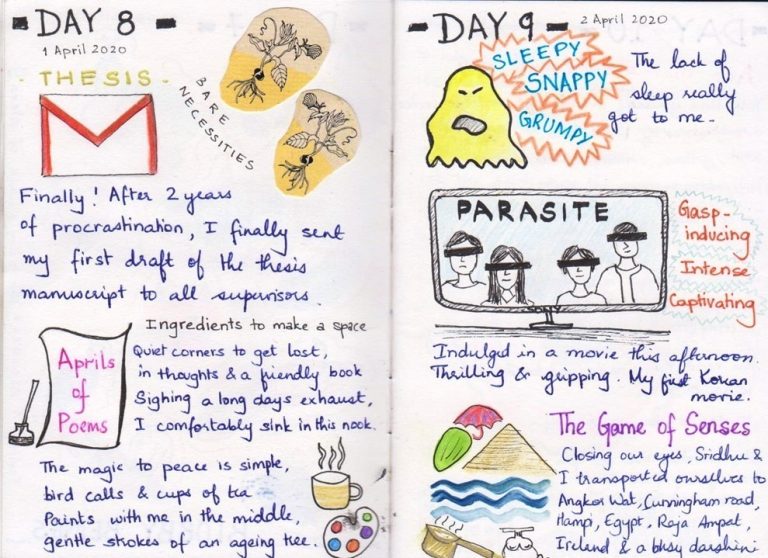

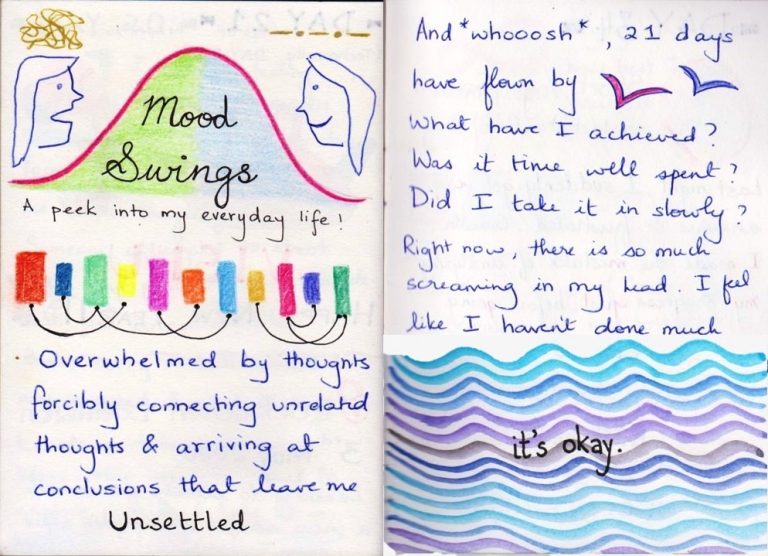

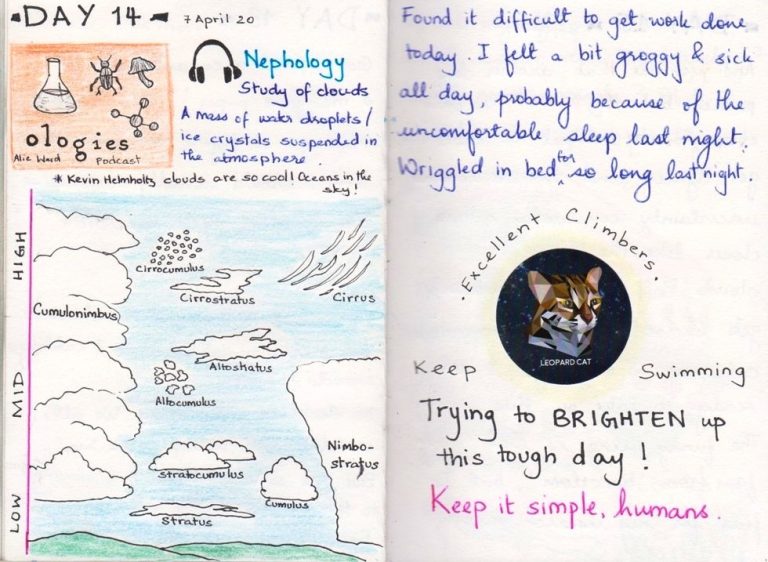

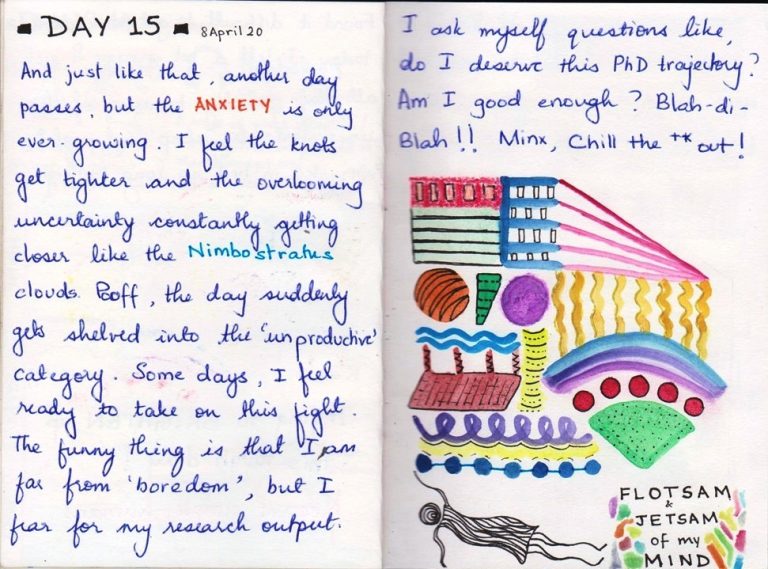

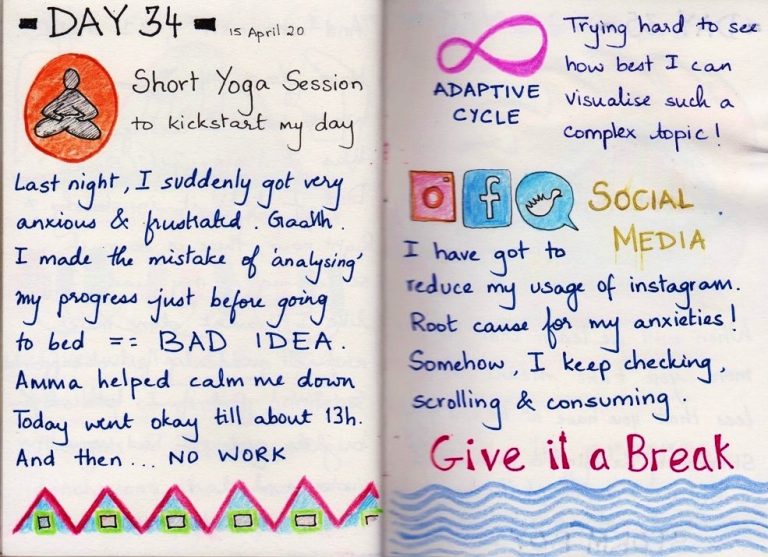

My days are filled with research, spending time with family, occasionally bombarded with the politics of this pandemic, visual journaling, Indian music lessons from my grandmother, reading books, listening to podcasts, virtual meetings, attending Instagram live sessions. So much to do. This push to do more often leaves me tired and anxious.

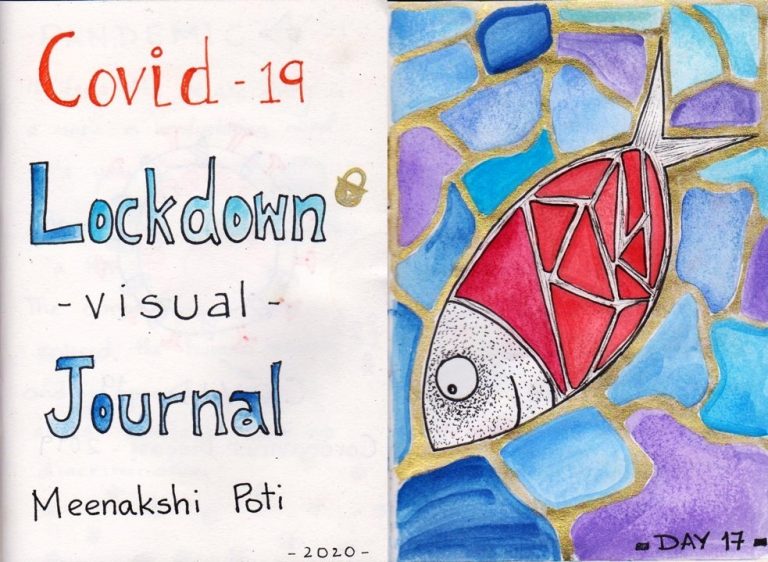

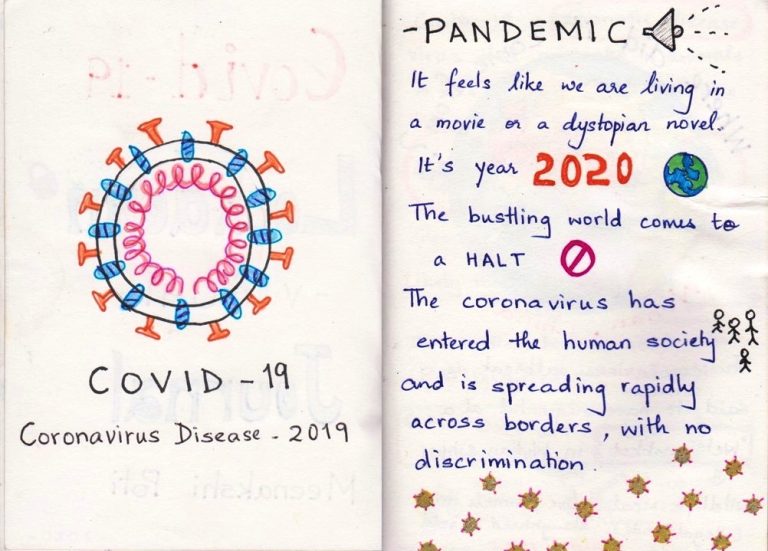

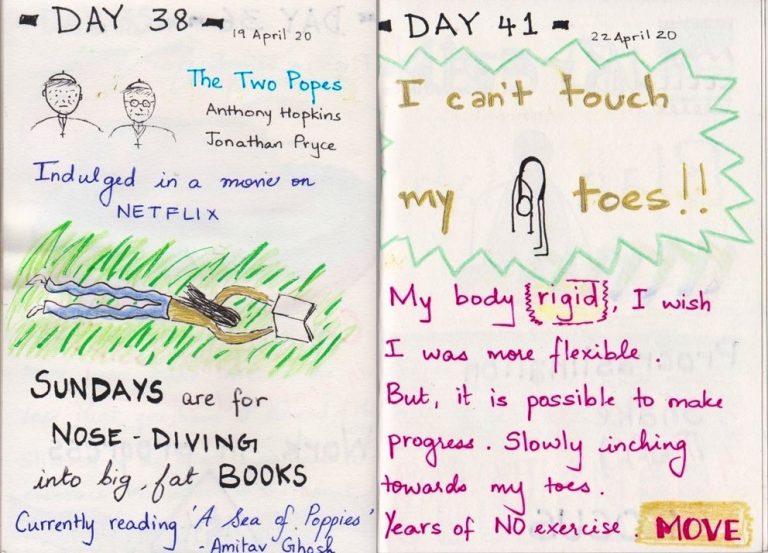

Just like that, 50 whole days have flown by. And I wonder why I feel like I did nothing. We are told all our lives that we must be productive and as academics, we measure it through research output. I have had smaller victories in the past month. Attending virtual hour writing sessions with Asha de Vos on Instagram has pushed me to write regularly. I remained dedicated to visual journaling, the only way to channel my frustration into written and drawn out thoughts. It helps give me perspective. I hope that the day I graduate (few years from now), I will look through this journal and remember the challenges thrown at me during my PhD.

I read that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted 80% of conservation careers. Every single one of us has a different coping narrative, and each of these is significant. It gives me reassurance that we are in this together. We make a generation of resilient academics, who will live through some pretty great uncertainty. I hope we do not rush back to ‘normalcy’. I have so much to learn from this pause.

What I do know is that when we come out of this, fieldwork will feel even more special – for the Andaman Islands are the motivation waiting outside my locked doors.

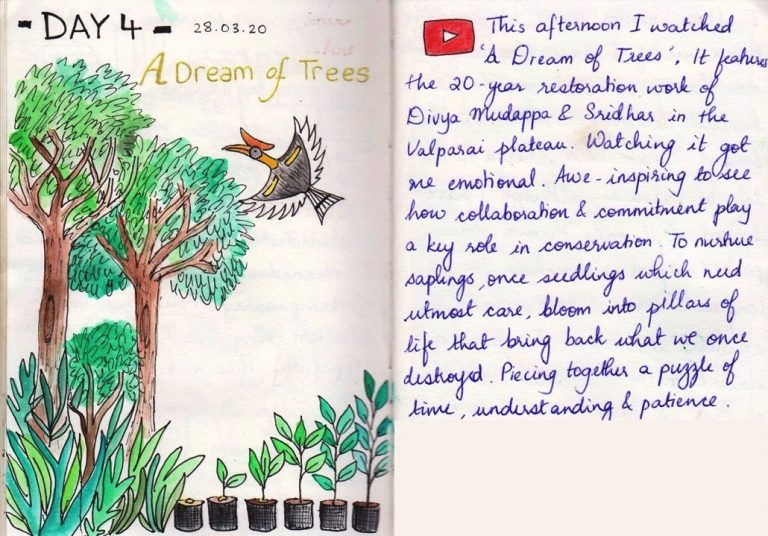

Excerpts from my lockdown journal: